I read a lot of books, mostly speculative fiction. This is meant to be a personal archive of sorts, but anyone who wishes to read and discuss is more than welcome to do so. I will mark any potential spoilers with tags.

Monday, January 31, 2011

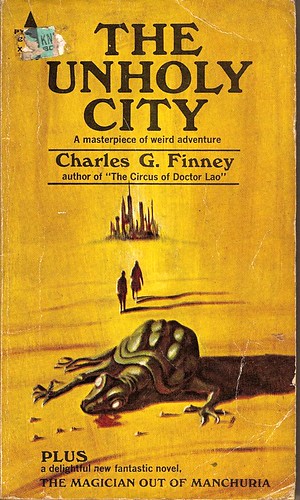

The Unholy City by Charles G Finney

So, I finished Charles G Finney's The Unholy City. It was a pretty short read, only around 120 pages, and I have to say I think I liked it more than his much better-known novella The Circus of Dr. Lao, which I also liked quite a lot. Though both are clearly written by the same man and share his odd sense of humor, the two books are quite different in execution; while Circus is set in a realistic version of Abalone, Arizona, and depicts the reactions of its everyday residents to the fantastic and magical traveling circus as it visits Abalone, The Unholy City is the exact reverse. Captain Malahide, resident of Abalone, sets out on a round-the-world trip, only for his plane to crash in a strange place, leaving him as the only survivor. He immediately loots the wreckage and finds himself in possession of a sizable sum of money, though practically nothing else. Soon after departing the crash site he comes upon a native, the loquacious Vicq Ruiz, who joins Malahide on his journey (once Ruiz realizes Malahide has a lot of money) with the intention of showing him around Heilar-wey, the titular city.

The city itself is not some fantastical fairy-city, however; it is essentially a bizarre parody of a modern metropolis, providing ample opportunity for Finney to mock various aspects of society. However, as with Circus, his parody is complex, but while in that book it was subtle, gentle even, here it is much more biting. One of the most powerful sequences is when Malahide and Ruiz sit in on a trial where a black man stands accused of murder; Finney initially describes him using exaggeratedly racist terminology ("paws" for hands, etc.), but when the man opens his mouth to testify he describes the events in question using the most poetic, vivid language possible, directly contradicting the initial impression of him as a big dumb brute (or Finney as a racist). Both attorneys continually interrupt with objections of the most irrelevant sort, while the judge struggles to stay awake. The sequence was certainly more relevant when it was written in the 1930s (lynching was still fairly common then), but I still found it quite tragic and darkly humorous at the same time. It's easy for some to claim that racism has been stamped out, and that railing against it is beating a dead horse and preaching to the choir; ignoring that how thoroughly it's actually been stamped out is subject to debate, it's nonetheless important to regularly familiarize ourselves with the worst aspects of society. That way we can learn to recognize and deal with them when they crop up in other forms (and believe me, in America we don't have to look very far to find them). Make no mistake, the claim that racism (or sexism, or any other form of discrimination) doesn't exist anymore is a victory for racism.

Still, things are usually lighter in tone, showcasing a really bizarre but also dark sense of humor, similar to RA Lafferty but lighter on the zany and heavier on the irony. While in Circus Finney kept his humor tightly reined in, here he really lets it run free. The Unholy City is just a hell of a lot of fun to read, despite being rather depressing overall. Malahide and Ruiz stumble through the surreal Heilar-wey in a seemingly eternal evening, drinking bottle after bottle of cheap liquor in bar after bar, and buying newspaper after newspaper without ever sleeping. They're nominally bent on striving toward the zenith of human happiness, as Ruiz has a premonition that he will soon die, but happiness seems forever out of reach. Meanwhile, various events are unfolding across the city, followed by the protagonists through radio and newspaper and rumor; civil war erupts as various social factions strive for dominance, and a giant tiger rampages throughout the city, characterized by Ruiz as "the wrath of God" (this despite the fact that he worships the Greek pantheon). There's all manner of weird symbolism of that sort, some of which Finney spells out explicitly, but with more of a sad shrug than a knowing wink.

In sum I would rate The Unholy City very highly; it tackles social issues with biting satire but in a complex enough manner that it never comes across as preachy or simplistic and it's often hard to determine what exactly Finney's position even is, if position he has at all. The protagonist claims to be a neutral observer in Heilar-wey who does not take sides and does not judge (to the disgust of nearly everyone), and that's most likely Finney's position as well. The edition I have includes Finney's The Magician of Manchuria, so that's what I'll be reading next.

Also, as a side note, don't confuse Charles G Finney the author with Charles G Finney the evangelist, as the latter's works seem to come up in book searches as often as the former's.

The First Law Trilogy by Joe Abercrombie

The characters were also very well written, consisting mostly of violent, conflicted people with checkered pasts, but each is written quite differently with very different outlooks. Abercrombie does a good job of making them sound genuine and varied from one another, among other things through their habits of using certain phrases and other such mannerisms. There is angst, but honestly it was quite downplayed. Unlike most of these "doorstopper" fantasy series, I actually liked almost all of the characters, and I didn't dislike any of them. There weren't any POVs where I would read the first page and say "oh crap, not another so-and-so chapter," which is probably the most annoying part of most authors who employ the revolving POVs (even good ones, like GRRM). Most of the characters themselves aren't very original in concept, but Abercrombie takes the fantasy archetypes (powerful old wizard; battle-hardened barbarian; dashing, pretty-boy fencer; physically deficient yet mentally proficient man caught in the web of court intrigue) and builds them in interesting and unusual ways. The barbarian for example comes across as reasonable, level-headed, and sympathetic, despite being a generally murderous bastard. The contrast between the way he comes across to the reader from inside his head and the way he comes across to the other characters is very well done.

As for style, well...as with most of these modern "doorstoppers", the style is somewhat lacking, though better I think than GRRM's. The problem with these really long series I think is that consistently good style is very hard to sustain throughout, as it requires every single word to be selected with the utmost care. Instead the style is closer to the "transparent", with workmanlike descriptions and metaphors and dialog that set the scene and get the ideas across, only very occasionally intruding into the reader's consciousness as being exceptionally good or bad. The characters speak fairly believably, and he eschews made-up bullshit for real swearwords (fuck, shit, etc.), which seems to bother some people, but honestly I think that works out better in the end. Otherwise he would have had to affect some nonsense, whereas the more modern diction allows us to grasp relative social context much more easily. There are times though where the style falls a little flat, but with such a lot of material to cover I can forgive some editorial oversights. Abercrombie's style is probably at its best in the voices of the various main characters, though I feel he does lean a little too heavily on certain repetitive idiosyncratic mannerisms to establish character. One thing I did appreciate was how he invented his own sayings (or altered existing ones) for his universe, and rather than treating them as universally revered wisdom, characters react as you might if quoted an old chestnut like "a bird in the hand is worth two in the bush." If the real world has its cliche sayings, why shouldn't an invented one?

The plot really kept me on the edge of my seat, and while I was able to call some twists, there were always more that I missed. There were also some instances of intentional dramatic irony, where the reader is given clues to figure something out long before the characters do. Abercrombie juggles a lot of balls as is expected from this style of fantasy, but he manages to keep them all in the air as we go from one end of the world to the other as the Union struggles to keep itself afloat as it's beset by enemies on both sides as well as from within. More discussion of plot, but with spoilers:

*SPOILERS*

Some people I think weren't satisfied with the way it played out, but honestly I thought the ending was excellent. Logen for example managed to fuck himself around in a big circle into essentially the exact same position he was in at the very beginning, while Jezal got more or less what he wanted and then some, but it ended up being mostly a sham (even if he isn't aware of just how much of a sham it is). Despite that he's probably most moral of all. Ferro got some of her vengeance and the tools to get more, but basically chose the vengeance over everything else. Glokta probably gets the most undilutedly "happy" ending of all, while also being one of the least deserving from a moral standpoint. Of course the "big reveal" at the end is how much control Bayaz has over everything, the Union being essentially his puppet in his fight against Khalul (with the Gurkish Empire as his puppet), with economics being Bayaz's method of control and religion being Khalul's. A lesser author might have tried to kill Bayaz off and end his questionably evil tyranny, but instead the wizard reestablishes his iron grip. I called early on that Bayaz would be trying to put Jezal on the throne, but I didn't guess that he would be behind Valint and Balk and through them the entire Union, so that was cool. It was a very unconventional and realistic ending for the series, without any kind of unconditionally positive or negative outcome for any of the characters. Even West, though physically debilitated in a way similar to Glokta and possibly near death, is still a Grand Marshal.

*END SPOILERS*

Overall I was very satisfied with the series, it was a rip-roaring read of exactly the sort I was looking for, but with the added bonus of having a better sense of humor than I anticipated, as well as more depth. The backstory of the Magi, the Maker, Juvens, etc. was especially compelling, even more so because there were so many unanswered questions. While I wouldn't rank it among my top favorites, the First Law trilogy definitely has its place on my bookshelf and I don't doubt I'll be re-reading it eventually. It's nice to find a fantasy author still living and writing whose continued output I can look forward to.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)